The theory of eating the foods my ancestors ate for good health came to mind when I saw two board menus recently: a Hakka dinner menu planned by the Tsung Tsin Association in Honolulu, and the day’s local specials at the Heeia Pier General Store and Deli on Oahu.

They reminded me of a model for sustainability presented at the “Chefs & Farmers Facing Future” forum I attended last month: create tighter communities and make friends with your neighbors.

At lunch with Cousin Millie (see my 5/15/2011 post) she asked if we would be interested in joining the Tsung Tsin Association, an international club that practices and preserves the (Chinese) Hakka culture.

We have Hakka genes. Hakka people descend from the Han people and migrated at various times for various reasons from northern China to the south and beyond. Hakka people are still migrating. They are nomadic.

Cousin Audrey Helen and I decided we would go to the Sunday meeting in Chinatown (Millie couldn’t make it) to check it out—for Millie—and report back. What do they do? I asked. Millie said she was told they eat and learn about Hakka culture (in that order). I chuckled.

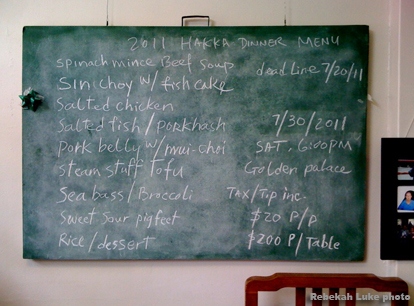

Everyone the world around agrees eating has priority. There it was on Sunday—a Hakka Dinner Menu posted in the clubhouse. There are no Hakka restaurants on Oahu, but the association found a restaurant in Chinatown that would cook the special menu for them. I thought of my friend Linda.

I met Linda in the Sunset magazine food test kitchens in the Seventies. I left the magazine after a couple of years, and she enjoyed a long career as food editor. When she retired in 2005 Linda planned a trip to China to research Hakka cuisine. It was an eating tour with all the arrangements made, right down to the chef of most meals, by Linda. She needed two more travelers to make up her party of 10 for a group rate, so DH and I did not have to think twice to accept the invitation. All we had to do was pay and show up in Beijing on the appointed day.

There are some basics to Hakka cuisine, but we also found that food took on added flavors from whichever region Hakka people lived.

Both Linda and I will have food books out in 2012—hers the product of her Hakka cuisine research, and mine a reprint of Everyone, Eat Slowly that has recipes and anecdotes of my family. The Tsung Tsin Association members might want copies, I’m guessing.

So that’s the Chinese side.

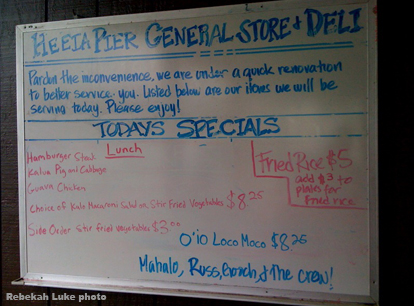

The other side is part Native Hawaiian. What’s native on the menu below is the “kalua pig,” “guava,” “kalo” and “o‘io.” And it wasn’t lost on me! These foods are not the traditional plate lunch fare. How refreshing to see what the new chefs like Mark Noguchi are coming up with.

The eatery that served up local-style food at the end of He‘eia pier, has reopened under new ownership/management, much to my delight. It had been closed for months since the previous owners retired. It is one of the very few ocean-front restaurants on the long coast between Kailua and Haleiwa. DH and I used to bicycle there from the studio for breakfast and watch the fishing boats come and go, or stop there on the drive back from town. Its scenic value is popular with artists.

From this menu, though the other diners recommended the guava chicken, I tried the fried rice. It’s a sautéed mixture of onion, green onion, carrot, egg, bacon, Spam—all diced finely—rice, and (I think) a little oyster sauce.

You can sit at the picnic tables or the small counter and listen to the folks talk story, or meander down the dock and watch the people fish for their own food. A man offered me some dried aku he made to go with my fried rice.

All this seems to fit in nicely with the message received from the “Chefs & Farmers Facing Future” food forum, organized by shegrowsfood.com and Leeward Community College, whose food service students wanted to give back to the industry that gives so much to them. The event brought together farmers, fishers, aquaculturists, ranchers, chefs, and media reps to explore promoting and using locally produced food for sustainability in our island communities.

The meeting started with the sobering fact that there is only about a 10-days’ supply of food here with most of it arriving by ship or plane.

What I took away from the meeting was the notion that to sustain we should form tighter communities and make new friends with our neighbors within them.

As the Hakka association that takes care of its clan. (My grandmother took care of her own family of 15 and neighbor bachelors by growing vegetables in her victory garden.)

Or the young creative chefs serving dishes with local ingredients, or the man who gave his fish to me, or my own developing garden that sometimes produces enough to share with the neighbors. It’s a great life.

Recent comments